In Person or Proxy to Mars and Beyond?

By Larry Klaes, Guest Writer, Red Planet Bound

In 1972, singer, pianist, and composer Sir Elton H. John (born 1947) released a song titled “Rocket Man”. This music piece, which was inspired by a Ray Bradbury (1920-2012) science fiction story of the same name, has an individual who sees his job in outer space not as some grand adventure as one might expect of a typical astronaut, but rather as ordinary and isolating.

Not only does this Rocket Man miss Earth and his wife living there, declaring “it’s lonely out in space,” he also says that “Mars ain’t the kind of place to raise your kids/In fact it’s cold as hell/And there’s no one there to raise them/If you did.”

As a life-long space and astronomy enthusiast, when I first became aware of this song, I was highly disappointed with its message. “Rocket Man” was a definite reflection of the counterculture era, where many rejected what they saw as the militant flaws and antiquated traditions of society which held back all but a select privileged few.

The space program fell into that category, being seen as a vehicle of a predominantly white male military-industrial complex. That it was also so publicly prominent only made it an even easier target for criticism, especially the kind that asked why we were spending money on sending humans to the Moon when there were so many problems on Earth that needed fixing first.

Even as a kid I knew this was an “apples and oranges” situation. The National Aeronautics and Space Administration, or NASA, was funded far less than most other government agencies of that era, a status that remains to the present day. Diverting all its resources to social agendas would have been a temporary band aid at best, not a real solution to modern civilization’s myriad of problems.

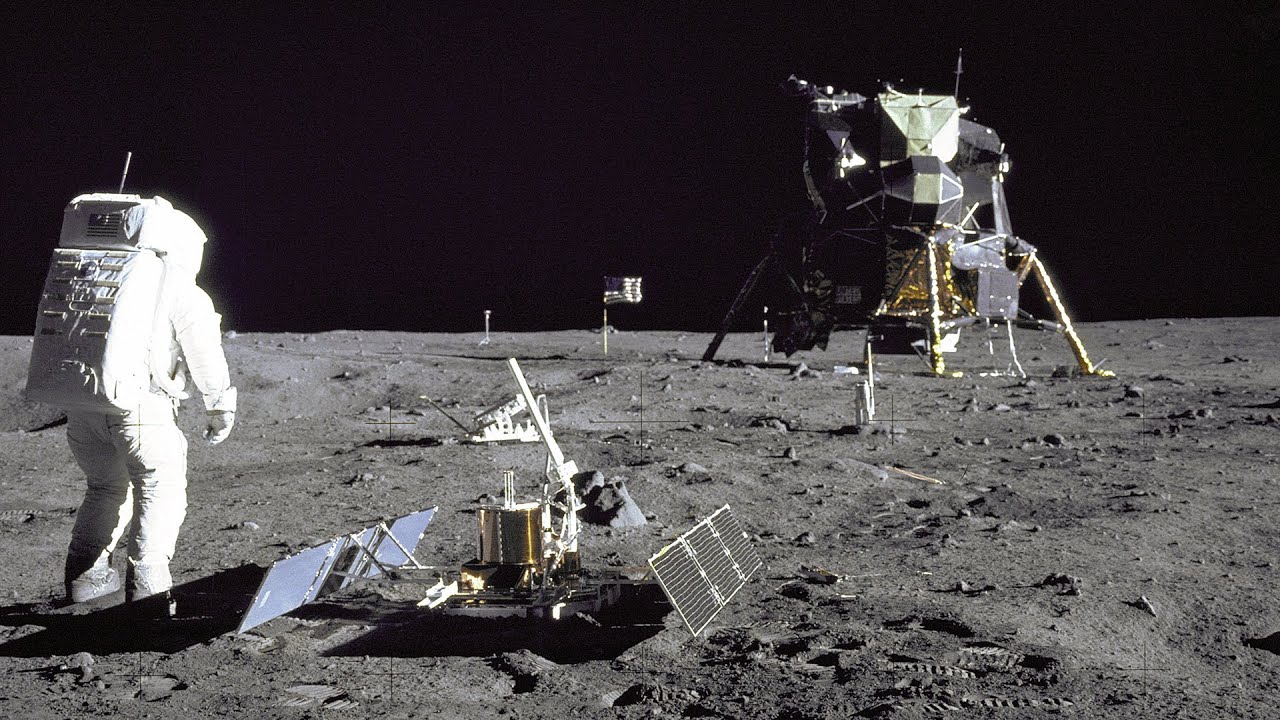

Nevertheless, the general public which had supported the early bold declaration of “sending a man to the Moon and returning him safely to the Earth” within ten years had undergone a significant sea change by the time NASA was actually placing astronauts on our planet’s nearest celestial neighbor at the end of the 1960s and into the early 1970s.

I had grown up in that era of the early Space Age when humans were actively circling Earth in preparation for launching representatives of our species to land on the Moon while robotic probes had begun to reveal other worlds such as Venus and Mars. I bought into the future storyline of the 1968 film 2001: A Space Odyssey and all those other pro-space entertainment media so prevalent then that humanity would almost automatically spread out and colonize first the Moon and then the other places in our Sol system, before moving on into the wider Milky Way galaxy.

I did not pay much attention to the geopolitical and social forces driving and affecting the space programs then, not just because I wasn’t able to fully comprehend them as a naive kid, but also because I felt they were only temporary issues, ones humanity would conquer as easily and rightly as we were doing with our move into outer space. After all, didn’t Star Trek show a future just a few centuries from now where Earth was united, we were flying about the galaxy in fancy starships, and dealing with all sorts of new alien neighbors as part of a collective called the United Federation of Planets (UFP).

So, when I heard Elton John warbling a very popular tune that said the starry realm was unpleasant, lonely, and not something good for bringing up children in, I was concerned his words would only add fuel to the fire that was already setting back our “manifest destiny” in the Final Frontier in the beginning of the 1970s.

The Apollo lunar program was already being defunded after the seventeenth mission, which in turn was killing off any plans for manned lunar colonies. The logical promise of sending humans on to the planet Mars after the success of Apollo, as soon as the 1980s it was being declared, was also placed on a shelf. No one was saying such missions were being cancelled, but it was pretty obvious that no one at NASA was seriously working on such an adventure by then, nor would they be any time soon.

Many in the West thought that America’s superpower rival, the Soviet Union, would pick up the gauntlet we had dropped and soon there would be cosmonaut boot prints on the Moon and Mars as they went on to become the dominant society throughout the Sol system and beyond.

Since then, a lot has changed. The American manned space program is not only picking up again, with real plans to settle the Moon with a new generation of astronauts as well as send these explorers on to Mars in the 2030s, but there is also a new Space Race of a kind, this time mainly with China. Upon jumping into this race with their first successful satellite launch in 1970, the “People’s Republic” now has a second crewed space station circling Earth while simultaneously conducting automated rover and sample return missions to the Moon and their first wheeled explorer conducting science on the Red Planet.

My attitude and views on our ventures into the Final Frontier have also changed over the decades. I am still quite the space supporter, but I am seeing it now as happening in certain different ways, in particular how we should venture into the void directly with fellow human beings.

When I used to read and hear certain professionals, whom I automatically assumed should have been big supporters of manned space exploration and settlement, publicly state that robots were better for exploring the cosmic void than human beings, I was indignant. They were going against the virtually predestined vision for our species expansion into the Milky Way galaxy and all those other stellar islands out there. Humans had to be an integral part of this future, otherwise our species and society would end up either stagnating or outright destroying itself in the very nest of its birth. No one in their right mind would keep a child in their crib and expect them to develop properly otherwise.

What needs to be understood is that when the Space Age began in the 1950s (or the 1940s if you want to count the first rockets that breached into the actual realm, if only briefly), humans were almost always the foremost choice for conducting all kinds of expeditions, be it on Earth’s surface, at sea, or in the skies. Space would have been no different then.

Yes, there were many satellites that went up carrying no living organic beings at all, but their mechanisms and computer “brains” were primitive by current standards. For example, Mariner 2, the first probe to successfully explore the planet Venus in late 1962, contained a computer weighing just over eleven pounds that was capable of “a total of 11 real-time commands and a spare… along with a stored set of 3 onboard commands which could be modified,” according to Oran W. Nicks, then Director of Lunar and Planetary Programs for NASA, as he described in his wonderfully written book Far Travelers: The Exploring Machines (NASA SP-480, 1985).

Even the twin Voyager space probes, designed, built, and launched into the outer Sol system on much more complex missions over one decade after Mariner 2, had multiple computers that were less powerful than a modern day automobile key fob. The onboard computers that helped land astronauts on the Moon with Apollo weighed over 75 pounds and had only 1,600 bits of memory in them, and they were specially designed by experts at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

On Earth, up until the first personal computers began showing up in large numbers in the 1970s, the majority of “thinking” machines were bulky, heavy, and most often required trained specialists to operate them. So, it is easy to see why most people back then assumed the best “computer” to explore outer space was the four pounds of “gray matter” occupying the skull of a functioning and properly educated adult human.

This technology has certainly changed since the first two decades of the Space Age. The average person now routinely works and plays with lightweight computers with storage levels and functionalities that would have been pure science fiction to their parents and grandparents. The machines currently exploring the Moon and Mars have autonomous capabilities that allow them to independently run their own missions while also being smart enough to avoid potential hazards in these alien environments.

As one may easily imagine, computing and robotic technologies for space are only going to improve in the coming decades to the point that one may rightly question the purpose of sending humans to distant worlds when much more durable and far less expensive and resource-demanding robots equipped with sophisticated Artificial Intelligence (AI) minds could do the same tasks.

Deadly Rays and Dwellings

Fewer resources and relatively cheaper funding aren’t the only reasons for sending machines over humans to explore other worlds. The cosmic environment beyond Earth is quite hazardous indeed for a species that has spent its entire existence evolving on a planet that is a virtual paradise for our biology compared to every other place in our Sol system (and who knows how far beyond).

Mars has often been considered the world closest in comparison to Earth, yet the least harsh places on the Red Planet make Antarctica look like a tropical island. Possessing only a very thin atmosphere composed mostly of carbon dioxide and no appreciable ozone layer or magnetic field, Mars is constantly bombarded by high levels of radiation from solar subatomic particles and cosmic rays. Solar ultraviolet rays also reach the Red Planet’s surface unabated. Meteoroids of most sizes are not deterred by the Martian air as they would be on Earth. Orbiting probes have imaged multiple results of recent impacts and the rovers have found substantiated meteorites as they roam the Martian dunes.

For Martian settlers to survive all these dangers, they would need to either develop structures with heavily reinforced radiation-proof roofs, cover their settlement with local regolith, or bury their dwellings deep underground. In most of these cases, unless humanity develops a type of transparent radiation shielding, the human residents will have to live without a direct view or easy access of their new home world.

Can humans stand being in an artificial environment underground on Mars for decades or even their entire lives? Down the road, settlements may be made large and luxurious enough to recreate the nature found on Earth, but the early pioneers will probably not be so fortunate. Will they last long enough psychologically to establish a permanent residence on Mars?

It is easy for those of us who are living now in the relative comfort and safety of Sol 3 to assume that those first settlers on our planetary neighbor can “tough it out” like the pioneers of the olden days did, but those ancestors who sought a new life did so on a world they were already adapted to physiologically. Martian settlers will require a great deal of preparation and mechanical services just to keep the climate of the Red Planet from outright killing them within minutes if they are ever exposed to the raw environment.

Terrestrial explorers and settlers also did not need to worry about dealing with the effects of a lesser gravity, for the pull of the mass of Mars for anyone on its surface is only 38 percent that experienced by those living on Earth. Not only will this eventually weaken those first settlers and their descendants, but it may create unexpected health issues and affect the way humans gestate in a mother’s womb and how they are born.

Our natural satellite has even less gravity and protection from the celestial threats already mentioned. There too settlers will have to live underground and deal with the same situations as their Martian brethren. The other nearby worlds with solid surfaces such as Venus, Mercury, and the Galilean also have their own unique challenges in addition to all those just described.

Circling Earth in Tin Cans

Human beings have been launching representatives of their species into the Final Frontier for just over six decades now. Yet outside of those handful of brief jaunts to the Moon now fifty-plus years ago, astronauts and cosmonauts have only experienced space directly in their biggest form as temporary residents of various space stations in perpetual fall around Earth, where their stays currently last between six months to one year.

Unlike those space explorers going to Mars, those in Low Earth Orbit (LEO) are but a matter of hours away from rescue and safety in the event of an emergency. This also applies to the ability to resupply the residents of a space station. These facts will have a definite impact on our first venturers who will be months to years away from any kind of help from Earth.

Space is Not a Convenient Species Safety Valve

One thing we cannot count on space serving us any time soon is as a method of reducing the overpopulation of humans on Earth, which at this moment is approaching eight billion individuals. The exodus numbers required to start alleviating the environmental pressure in that direction are not going to happen any time soon, assuming reducing the human population ever even becomes a goal in the first place. Besides, we cannot just “displace” a fraction of our species without serious preparation first and this will only loop us back to the issues I have already addressed, the ones that will decide whether we can permanently settle space or not.

Of course, none of these obstacles may deter those individuals, organizations, and nations who are determined to live off Earth despite the various costs. One may easily envision the super wealthy constructing their own space habitats in what might be considered the ultimate gated community. Others may turn a hollowed out planetoid or comet into a WorldShip of multigenerational space ark and head off into the wider galaxy with their chosen acolytes, their fates left entirely in their hands.

Should space become profitable, corporations will most certainly start moving humans and machines out there. Will conditions for such laborers be better than on Earth, or will it be a case of the old phrase the same day, just a different song? While more robots and other artificial devices will be required to literally mine the Final Frontier, corporations may still find humans to be overall much cheaper to utilize to collect resources and maintain the various services envisioned in space. This would also include the costs of replacing such laborers when the situation calls for it.

Adapting Ourselves to the Reality

As we are such small creatures compared to the vastness of space and its many wild and dangerous environments, would it perhaps make more sense to change ourselves rather than try to make other worlds more like Earth?

Terraforming Mars, Venus, and even the Moon have been suggested for roughly a century now as a way to expand humanity to the stars, but would it work? At the least it may take centuries or more to convert an entire planet into one resembling what we have now. One aspect we may not be able to change that could affect such a project is that except for Venus, the other worlds will continue to have less mass than Earth.

Now imagine beings who could live and work directly in outer space, or on any number of moons and planetary bodies. It will very likely be easier, cheaper, and quicker to adapt humans to other places than try to change an entire world to suit our physiological needs. This would certainly ensure the survival of our species, even if they are not like we are now. This would not be all that unusual considering how different we are from our distant prehistoric ancestors, and rather few are put off by this fact.

As an additional incentive, note how humans already spend billions in unrelenting efforts to make themselves better in all sorts of ways. Such desires have only increased as our technologies for these improvements have gotten better. Space may become the ultimate reason for human improvement and durability. Perhaps this is all part of the process of our evolution, only we are facilitating the matter faster than nature has done in the past and in the direction we want it to go.

We should not be disheartened by the fact that exploring and settling space with our species as it currently is may not be the best way to go in the really long term. Instead, with our new capabilities and knowledge, humanity can supersede what we once thought was the best way to expand ourselves into the Universe and do so in a way that will ensure our survival and success.

So, Rocket Man, you may have been ultimately correct regarding the expansion of humanity into space, but for reasons ultimately different than you could have possibly imagined. This is with no offense intended, as we are all products of our time and place. The good thing is that we can and will evolve our collective understanding of existence, which in turn will allow us to adapt for the future.

The Mars Society would like to extend its appreciation to Larry Klaes, our guest writer, for contributing this article to our organization’s space advocacy efforts. A veteran technical writer, Lawrence will draft occasional pieces about Mars, space exploration and technology.

Lawrence Klaes is an author of science and nature essays and is the former Editor of the EJASA (Electronic Journal of the Astronomical Society of the Atlantic). He was also the Editor and Co-Producer of SETIQuest magazine, only the second periodical devoted to the subject of searching for extraterrestrial intelligence. Larry’s written works may be found on the Centauri Dreams blog site.