It’s time to consider alternatives to sample return

By Robert Zubrin, Space News, 12.07.23

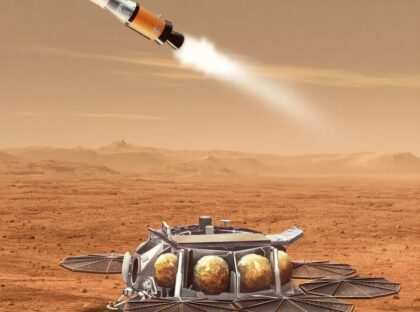

NASA’s robotic Mars exploration program is in crisis. A recent review of the plan of its flagship Mars Sample Return (MSR) mission pegged its cost at $10 billion, a price tag that threatens to preclude funding any other exploration missions to the Red Planet for the next decade and a half.

While the decadal plan issued by a National Academy of Science committee identifies the MSR mission as the top priority for NASA’s Mars exploration program, given the cost and schedule numbers now available, it is time for the rest of us to question whether the program of record still makes sense.

Let us consider the alternative. For the same $10 billion now projected to be spent on the MSR mission over the next 15 years, we could send 20 missions averaging $500 million each in cost. These could include landers, rovers, orbiters, drillers, highly capable helicopters, and possibly balloons or other more novel exploration vehicles as well. Instead of being limited to one exploration site, these could be targeted to 20 sites and carry a vast array of new instruments provided by hundreds of teams of investigators from around the world.

What is the best Mars exploration program that

the American people can buy for their $10 billion?

All options should be on the table.

NASA claims that its Mars exploration program aims to search for life. However, the agency last flew a life detection experiment to Mars in 1976. With a robust program of this type, we could fly a dozen life detection missions to various locations and not only test the surface soil in various new ways for life but drill down to search much more life-favorable strata beneath the surface.

With a robust program of this type, we could do many other things. Helicopters of other aircraft could carry sniffers to search for methane vents, and study thousands of surface locations each time they land. Such craft could also scan the subsurface of the planet for caverns and hydrothermal systems using ground penetrating radars (GPR). The power of a radar return signal goes as the inverse fourth power of the distance from the transmitter to the target, providing an eight-order of magnitude advantage to aircraft over orbiters for this type of exploration. Most of Mars is underground. We should see what’s there.

These are just a couple of examples. For every instrument flown on Curiosity or Perseverance, there were 10 other good ones proposed that had to be excluded for lack of payload capacity. With a robust program of this type, many more instruments would get a chance to be flown. Not only that, but with plentiful missions in the queue, it would be possible to use the information provided by early missions to improve the engineering design of the exploration vehicles and identify the best instruments and target locations for follow-up investigations.

To read the full article by Dr. Zubrin, please click here.