By Evan Plant-Weir

The scope and scale of Mars settlement is so significant that it can defy our intuitions.

Generally speaking, thinking about endeavours on this scale does not come naturally to us. Especially for those that are new to the idea, it can feel detached from practical reality.

The trick to shrinking this unwieldy concept down into an accessible format, is found by thinking a little bigger. We have to consider it within the broader context of history.

In the Northwest corner of Italy, the small valley town of Aosta sits tucked against Switzerland and France. This alpine settlement was once home to a Gallic people known as the Salassi, who were driven out by the Roman empire in 25 BC. To commemorate this victory, the Romans built the Arch of Augustus, a monument that still stands over the city entrance today.

Much later, In the mid-1700s, the artist and archeologist Giovanni Piranesi made an etching of this monument. It portrays a group of 18th century Aostanis shuffling about in the shadow of that then-dilapidated structure.

Two centuries after Piranesi’s death, and shortly before my birth, a print copy of that image was mounted on the wall of my family home. That depiction of an empire’s half-forgotten monolith – already ancient to those nameless figures – was almost certainly one of the first things I ever saw. It is among a set of influences that would ultimately instill in me a visceral realization:

We are all fundamentally tied to the ceaseless and volatile course of history.

This is not only to say that I became aware of human history in an academic sense, but rather that I developed a palpable, concrete intuition for the implications of that simple reality.

When I look at Piranesi’s etching, I don’t just see a representation of some abstract past, I feel the transience of a real moment in time bleeding across 250 years and arriving at my present experience.

Just as the Salassi became a figment of history for the Romans, and the Romans for the Aostanis, I know that we are already nameless figures shuffling about below the ancient monuments of someone’s history.

The next two thousand years will pass by just as swiftly as the last, and when that moment arrives, it will feel equally real to somebody as this moment does to you now.

Many of us have experienced this at one point or another, a sense of closeness to the past or future that seems to bridge the years in between, and to imbue another time with as much reality and consequence as the present.

This is the feeling of genuine, existential awareness that we are a meaningful part of the historical context.

It is in the application of this awareness that we can fully grasp the significance of a multi-planetary future. Conversely, it is the failure to appreciate the implications of our place in history that can explain much of the opposition to this goal.

Crossing the Conceptual Divide

The vast distance between here and the red planet is difficult to fathom with any intuitive meaning. It is as if that physical gulf is so great that it surpasses some cognitive threshold, beyond which things just don’t feel real.

Similarly, the timescales involved in Mars settlement are long enough that they can defy a sense of relevance. In contrast to the short timeframes of daily life, the task of adopting a new planet can feel a little overwhelming or unrealistic.

This sense of surreal detachment for things beyond our immediate time and space is an illusion, born in an evolutionary process that simply did not require us to develop an intuition for reckoning on this scale.

Evidence of this mirage can be found even in the rhetoric of professionals actively engaged in the space exploration community. Therein, the subject of Mars is frequently coloured by a hue of abstractness, as though it were a mathematical formula or philosophical construct; useful as a platform for academic and technical inquiry, but with uncertain real-world consequence.

This illusion is most evident, however, in the usual criticisms levied against the pursuit of a multi-planetary future. The debate is consistently harangued by arguments predicated on the belief that Mars is too difficult, too dangerous, and too far away.

Detractors offering these arguments are almost always approaching the situation with historical tunnel vision.

What does “too dangerous” mean in the context of human history? Relative to the daily life of an average person working a safe job in the developed world, the first crewed missions to Mars certainly will be quite dangerous.

In comparison to most human labour ever performed, however, it is truly difficult to see how we could qualify that endeavor as “too dangerous”. It is especially hard to see the logic of that position when considering the immense value provided to all of us by space exploration.

Crewed missions to Mars will be undertaken willingly by highly trained, well paid experts, engaged in the greatest passion of their life. They will travel in cutting-edge spacecraft engineered by brilliant minds, carrying modern medicine, 3d printers and freeze-dried macaroni with little chocolate desserts. They will have access to robust (though delayed) lines of communication to nearly every subject matter expert on Earth, and virtually every system critical to their safety will have multiple backups.

Contrast this with the dank, rat-infested and scurvy addled misery of an ocean voyage in the 17th century, during which the sailors are driven to eat their boots by starvation. Compare it with the 16-hour workday of an industrial age factory labourer, toiling in excruciating heat amid unguarded machinery that regularly inflicts serious injury. Consider that still, to this day, millions of people are necessarily bound to grim and hazardous livelihoods.

Not only is going to Mars less dangerous than much of human drudgery throughout the ages, but the reasons for doing it are so profound as to make the danger well worth it.

That anyone could think the risk of a multi-planetary future outweighs the reward, surely indicates that they have failed to consider the danger inherent to life on Earth in the context of history.

Imagine for a moment a coal miner living in 5th century China, who has slogged through a lifetime of unthinkable danger and discomfort, with broken back and blackened lungs, all in order to feed their children in hopes of a brighter future.

Pause to speculate as to their reaction if we could tell them that – one day – their descendants would have the opportunity to go to the stars, but that we would choose not to go because people in clean suits, sitting behind comfortable desks would decide for the rest of us that it’s too dangerous.

What was the point of those millennia of struggle towards a more stable and secure future if we aren’t even going to attempt things like travelling to new worlds to take on new beginnings?

The illusion that Mars is “too difficult” is similarly cured by a sober accounting of human history.

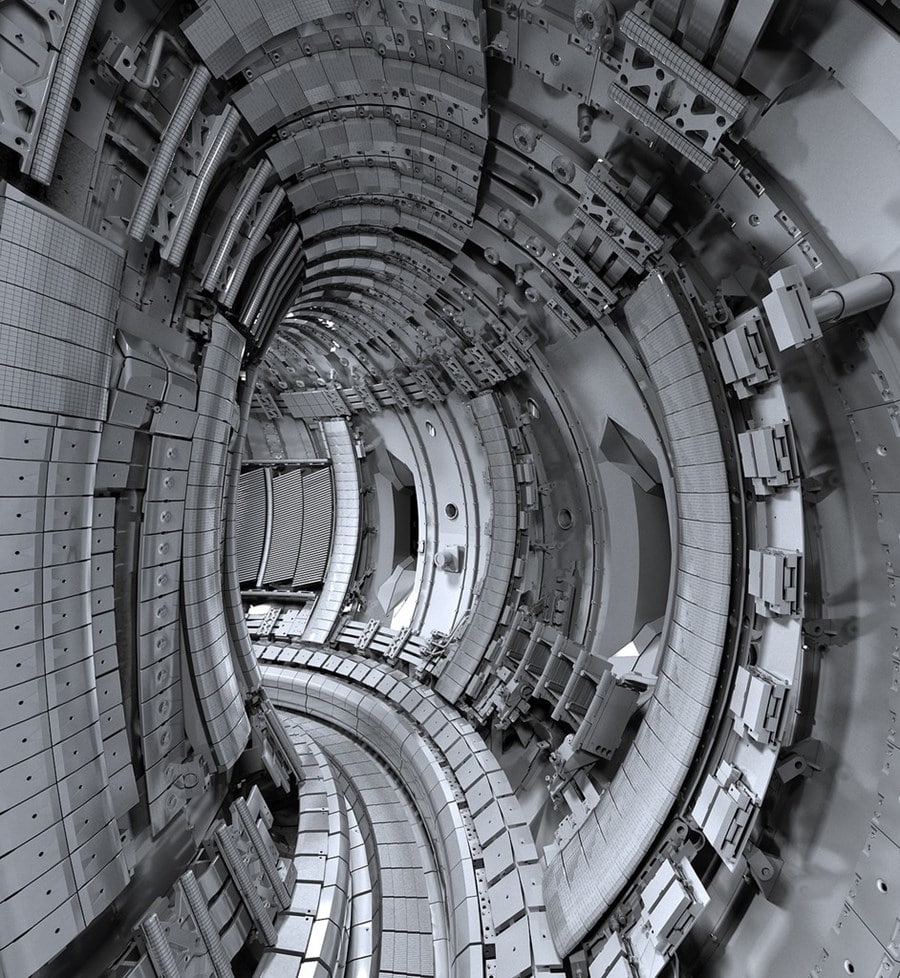

Even the most cursory review of technology developed over the last century alone should remedy this baseless misconception. The notion that we can construct prototype fusion reactors, manage global trade logistics and perform gene sequencing, but not learn how to build mud brick radiation shelters on Mars, is a true demonstration of losing perspective.

The Moon and Mars present many of the same technical challenges to crewed flight. Actually, in some regards, it could be argued that the Moon is a more difficult spacefaring environment. And yet, twelve astronauts have visited the lunar surface via six separate missions, and none of them died as a result.

It took a mere ten years to turn the Apollo program from a dream into a reality, using 1960’s engineering. With the technology available to us today and over the coming decades, we are considerably more capable.

Certainly, settlement of the red planet presents some unique challenges, but where lies the immovable obstacle on that path? Are we really to believe that we can innovate our way out of the stone age and onto the Moon, but no further?

Once again, this illusion of supposed insurmountably is understandable only if we approach the question with historical horse blinders on. To believe that Mars settlement is beyond our ability as a species, is to lose sight of the overwhelming evidence to the contrary found in 5,000 years of human innovation and creativity.

Bridging Millenia

By framing Mars settlement in the context of history, we can bring it within the boundaries of our intuition for what feels real and meaningful. Further, in the light of our proven resilience and ingenuity as a species, we can see that there is every reason to expect that we would withstand the rigors of that challenge.

What’s more, by weighing the implications of a multiplanetary future in historical timescales, we can begin to appreciate the potential available to us on this path.

In previous writing, I address the importance of Mars to the survival of life from Earth. Given that saving the light of consciousness from annihilation is possibly the most important thing we will ever do, it bears repeating. There really is no way around the fact that a single-planet existence is almost certainly a death sentence for life on our home world, given enough time.

In the words of Randall Munroe,

“The universe is probably littered with the one-planet graves of cultures which made the sensible economic decision that there’s no good reason to go into space…”

This is, however, not the only compelling reason to undertake that mission. By learning to live on new worlds, we can open the future to a richness and diversity of human experience on a scale that is utterly unprecedented.

It is important to emphasize that in learning to live on Mars we will necessarily develop a general proficiency for space faring. There is a profound implication here which is easy to miss, so bear with me as I drive this point home.

The technologies needed to live on Mars will provide us with the building blocks to go elsewhere in the solar system, and possibly beyond.

In a very real sense, the red planet is our gateway to the stars.

The difference, then, between choosing to stay on Earth and taking on the challenge of Mars, is vastly more consequential than it might at first seem.

If we can stretch our intuition a little further, out beyond the coming centuries and into the next millennia, the contrast is staggering.

On one hand, human life stays relegated to a single planet. The entirety of our existence remains bound to the physical limitations of one small island in the unimaginably vast archipelago of space. The depth and breadth of human experience is hobbled to a tiny fraction of its potential.

On the other hand, we can learn to live on other worlds. In so doing, we open the door to a capacity for Earth-originating life on an astronomically greater scale. As we push out into the endless opportunities beyond our atmosphere, the multitude of new and unique challenges that await us will drive the growth of our species to heights we cannot currently imagine.

The amount of creativity and inspiration, the volume and variety of human relationships, the immense social, economic and cultural dynamism that would follow is beyond measure.

And, if you find it difficult to achieve a sense of reality or meaning when contemplating this distant future, pause to consider that the length of time elapsed since the Arch of Augustus was constructed, is likely greater than the time it would take to see a self-sustaining civilization on Mars.

That ancient monument, that you can still see and touch, originated in a time that is further away from our present moment than the establishment of the first city on another world.

The red planet is not an abstraction. It is every bit as real and important as any other aspect of our history, and just as we have crossed the millennia with courage and ingenuity, so too will we cross the divide between worlds.

Evan Plant-Weir HBSc, is co-founder of The Mars Society of Canada. He is a passionate space exploration advocate, creative writer, science communicator, and content creator. Access Evan’s LinkedIn Page.